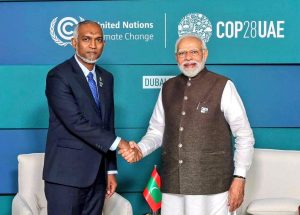

On December 1, following his first meeting with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi on the sidelines of the COP28 summit in Dubai, Maldives’ newly elected President Mohamed Muizzu announced that India had agreed to withdraw troops from his country.

Muizzu’s election campaign had focused on an “India Out” plank. A day after his electoral win in September, Muizzu, who is widely seen as pro-China, had asked India to withdraw its military personnel from the Indian Ocean archipelago. He also said that his government would review bilateral agreements between India and the Maldives.

A close associate of former Maldivian President Abdulla Yameen (2013-18) under whom Maldivian relations with China grew rapidly, Muizzu defeated the pro-India Ibrahim Solih (2018-2023) to become the Maldives’ new president.

During the meeting in Dubai, Modi and Muizzu decided to set up a core group to strengthen their partnership.

According to Indian sources, the two countries are engaging in talks on how to keep the helicopters and aircraft gifted by India to the Maldives operational. These have played a major role in helping Maldives with disaster relief and humanitarian operations. Most of the 77 Indian military personnel whom Muizzu wants out of his country were involved in operating these aircraft.

Unlike his predecessor Solih’s “India First” policy, Muizzu’s “India Out’” campaign was aimed at reducing Maldives’ dependence on India.

In the weeks since his swearing-in as president, Muizzu has been looking for new partners. He has broken away from the Maldivian convention of new presidents visiting India for their first foreign trip. He opted to visit Turkey and then the UAE instead. He is yet to visit India.

In an article in Indian Express, noted Indian security analyst C. Raja Mohan writes that “Smaller states of the [Indian] Subcontinent are becoming attractive geopolitical targets not only for big powers like the US, China and Russia but also for middle powers like [Turkey].” These smaller states are equally interested in new partnerships. The change in Malé’s strategic orientation under Muizzu can be viewed as a natural inclination of smaller countries to diversify their security partnerships.

Mohan cautions India to be wary of Turkey or Qatar or Pakistan’s attempting to draw Malé into their Islamic orbit, especially at a time when geopolitical differences are increasing between Ankara and New Delhi. He suggests that New Delhi should be patient in its engagement with the Maldives. India can work with like-minded partners in the Middle East like the UAE and Saudi Arabia to prevent any potential destabilization of the Maldives by Türkiye.

An important aspect of Maldivian foreign policy under Muizzu that merits attention is how he will deal with the two geopolitical rivals, India and China.

The two countries’ interest in the Maldives stems from its location close to strategic Sea Lanes of Communication (SLCOs) for maritime trade between West Asia and Southeast Asia. This underlies China’s rising interest in Maldives and its growing presence in the archipelago. This has in turn triggered apprehension in India, prompting fierce competition between the two countries.

Congratulating Muizzu on his election victory, the Chinese government expressed its keenness to promote the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects in Malé. Muizzu expressed his government’s eagerness to bolster the bilateral ties in multiple fields, including BRI. At a conference of the China-sponsored Indian Ocean Region Forum (IORF) in December, new Maldivian Vice-President Hussain Mohamed Latief called for all-inclusive cooperation in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) devoid of any factionalism, a “possible” reference to the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy, which is aimed at countering China. Latief, who is the first high-level official to visit China since Muizzu took charge, also acknowledged China’s role as significant for Maldives’ progress in recent decades.

Consequently, India faces several challenges in the Maldives during Muizzu’s tenure. China can be expected to make huge inroads in Maldives even as India’s military stakes and investments are expected to reduce. A rise in anti-India terror activities emanating from Maldivian soil is possible. New Delhi has reaffirmed its multifaceted partnership with the Maldives but has reiterated its opposition to BRI.

India may even shelve its plan to include Maldives in the Indo-Pacific strategy for some time. Experts believe that India will focus more on wielding soft power to retain influence in Maldives.

Since Maldivian independence in 1965, except with few hiccups, New Delhi and Malé have enjoyed a close relationship, further shored up by strong religio-cultural and commercial links. Bilateral ties suffered a setback in 2012 when the then pro-India President of Maldives Mohamed Nasheed was forced to step down from office and the pro-China Yameen came to power in 2013.

In 2014, when Narendra Modi came to power in India, his government adopted a “Neighborhood First Policy,” propelling the Maldives and other South Asian countries to the top of India’s foreign policy agenda.

India’s presence in the Maldives is significant. In the defense sector, Maldives is dependent on India due to its lack of capacity to safeguard itself and its resources against a variety of threats. India has extended the Maldives’ strong military support to assert its role as a ‘net security provider’ in the Indian Ocean. Economic relations have strengthened over the years with India extending loans on easy terms to fund its infrastructure development, including the Greater Malé Connectivity Project. Indeed by 2022, India was supporting nearly 45 projects in Maldives. Around 30,000 Indians are living and working in the Maldives, and India has contributed immensely to capacity building and humanitarian assistance operations there.

To put it succinctly, India has been a close partner of Maldives, a longstanding donor and the first responder in crisis situations.

Muizzu would therefore not like to forfeit India’s goodwill towards his country as it will hurt Malé more than New Delhi. In fact, during the recent meeting between the two leaders, the Maldivian side acknowledged the utility of Indian platforms in Maldives.

However, domestic politics has often influenced Maldives’ foreign policy. It has driven anti-India sentiment in archipelago. But at the same time, it’s Malé’s internal politics that often decides its foreign policy including its nationalist attitude towards India.

While Muizzu has shown interest in China, he will have to walk a diplomatic tightrope between India and China, according to experts. Despite current uncertainties, Maldives will not completely lean towards China since the former has already been a victim of the latter’s debt trap.

This will make Muizzu adopt a more independent, balanced and diversified foreign policy rather than a pro-China one.