In early February, health officials in Singapore were stumped by a sudden spike in novel coronavirus infections. A majority of the cases came from two church-related clusters. Was there a connection?

Armed with activity maps, tracking data, and an experimental antibody test, the Ministry of Health systematically connected the dots until they zeroed in on the missing link: a Chinese New Year gathering on Mei Hwan Drive where a 28-year old man known as case 66 picked up the virus from an older couple (case 91 and case 83) who had visited The Life Church and Missions church. Case 66 was an employee at Grace Assembly of God and passed on the virus during staff meetings at the church, where the infection spread and became the largest COVID-19 cluster in Singapore.

The discovery of the link between the groups was an important breakthrough confirming that the virus was contained, dispersing through a series of known events rather than widespread community transmission.

A graphic from the Singapore Ministry of Health depicts the connections between COVID-19 clusters.

No country does “contact tracing” better than Singapore. Scientists from Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health noted in a recent paper that the city-state had a “very strong” track record in this type of disease surveillance and their ability to detect cases was three times higher than the global average.

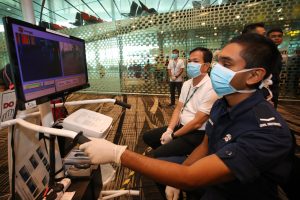

The process begins at the hospital where patients are interviewed in order to create an exhaustive map of activities and a list of close contacts. A Ministry of Health official told The Straits Times: “The mapping is detailed, 24 hours, minute by minute, with no gaps.” Even the police pitch in with tracking data.

Based on the map, close contacts are identified and either monitored or quarantined to prevent the spread of the virus. A “close contact” is anyone who has been within two meters of an infected person or spent 30 minutes with them. Apart from family and friends the list could also include service providers like waiters or taxi drivers. More than 3,000 close contacts have been quarantined since tracking began and the Ministry of Health provides daily updates on how many remain under observation.

Impeding the work of contact tracers is a serious offense. A Chinese couple from Wuhan are facing penalties ranging from stiff fines to jail time for providing false information about their whereabouts.

But even a robust contact tracing system can be thrown off track by a fast-moving virus. One early lapse occurred with case 91 (the 58-year old woman at the Chinese New Year gathering) who visited the emergency room in a public hospital. According to the case history which was made public, “Case 91 had gone to the emergency department at Sengkang General Hospital earlier on 26 January with symptoms consistent with COVID-19.” But since she had not traveled to China, she was not tested. Her husband, who later came down with the virus, also escaped detection. Hospitals have since fine-tuned their procedures and are “much more vigilant,” said Dr. Kenneth Mak, director of medical services at the Ministry of Health.

Singapore’s ability to adapt quickly during an epidemic is one reason why global health experts have called the city-state “the model to emulate.” Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the World Health Organization, said Singapore was “leaving no stone unturned” in its effort “to find every case, follow up with contacts, and stop transmission.”

Tough laws and semi-invasive methods coupled with cajoling and cheerleading are Singapore’s way of handling epidemics in the post-SARS era. In a country obsessed with disease prevention, even Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong tweets about having his temperature checked multiple times a day.