Russia’s economy made out better than expected during the crisis last year. Aggregate GDP only dropped in the range of 3.5-4 percent despite worse forecasts. The Kremlin made do with relatively limited crisis spending measures, betting on China and other economies to recover quickly enough to isolate the economic damage instead. Although oil and natural gas – still Russia’s primary exports – took a shellacking until the last few months of the year, Moscow lucked out: A broad range of non-oil and gas commodities including gold entered a bull market by summer, aided by a $500 billion fiscal stimulus package in May from China.

China’s spending was geared toward investment and businesses, many of which produce goods for export or build homes and infrastructure. While economies the world over including Russia struggled with multiple waves of infections, lockdowns, and constraints on services demand, China’s exports of goods surged to record levels by December – a surplus of $78 billion in December alone. Ironically, it was the under-development of small and medium-sized businesses and services in the Russian economy that spared the Russian policymakers a much steeper price tag in stimulus spending.

The good news, however, stops there.

For the past decade, China has done more than any other economy to sustain Russia’s oil export earnings and thus its economic model – China alone accounted for just over half of the growth of global oil demand between 2008 and 2019. China’s consumer recovery has lagged behind that of its industrial recovery from the worst of the crisis, and while the economy is finally approaching balance, it’s still locked into a structurally slowing growth rate.

Refining giant Sinopec is now forecasting China’s petroleum product demand to peak by 2025 because of the impact of coronavirus and accelerated adoption of electric vehicles. No one is certain of what comes next for energy markets, but one thing is clear: This shock is nothing like the Global Financial Crisis and the odds of a longer-run return to high oil prices are slim at best. The Kremlin has exhausted Russia’s growth potential with its current economic structure. As China’s role underpinning energy demand and the composition of its growth change post-COVID-19, Moscow will have to grapple with its domestic policy failures.

Supply-Siders of the World, Unite!

Any substantial economic recovery in Russia requires higher oil prices, realistically in the range of $60-65 a barrel, in order to generate a mix of excess budget revenues and higher intermediate demand for goods and services to sustain the stagnant type of growth seen in 2018-2019. Oil is currently above $50 a barrel, but concerns about Europe’s vaccine rollout woes and more infectious strains of COVID-19 are weighing down any positive outlook. Russia’s supply side management of the oil market within OPEC+ helped stabilize the oil market, but exacerbates the problems created by taking part in production cuts. They’ve become a necessity to manage budget deficits, the ruble exchange rate, and the health of the country’s currency reserves and banking sector by pushing up prices. But the cuts reduce domestic demand for goods and services, spilling over into other sectors including manufacturing, which experienced its first net contraction since 2009 last year. Ensuring oil price stability by paring back output ends up squeezing growth because it suppresses domestic demand.

Russia’s trade surplus reflects its dependence on external demand for its main resource exports to drive growth and its business cycle. What’s interesting is that just as oil and gas prices began the slow process of stabilization in May to June, Russia went from surplus to a trade deficit with China. The deficit then widened, reaching $5.5 billion for the month of November. It seems that China’s exporter-centric stimulus pushed more production into Russia, likely aided by a better exchange rate than the euro against the ruble. But a deficit in the longer run is a problem for Moscow. The trouble stems from what Russia’s trying to export more of, how it affects its domestic economy, and how bilateral trade interacts with Russia’s energy export dependence.

Gone Agro

Normally a bilateral trade deficit is irrelevant. Countries’ trade balances reflect how much they produce versus how much they consume and whatever excess or deficit they have with one country gets distributed with others. But in Russia’s case, a trade deficit with China reflects a post-Crimea shift: European companies as well as Asian firms with supply chains in China moved to grab market share or relocate production from Europe after the ruble devalued in 2014-2015, the West applied sanctions, and Russia then applied counter-sanctions on agricultural imports from Europe. Deficits with China are harder to make up elsewhere as Europe’s prolonged recession and environmental policies are accelerating the destruction of demand for Russia’s energy exports longer-term. That means more agricultural exports – one of Russia’s few areas of competitive advantage – are needed to restore more balance for trade with China.

But there’s a problem with agricultural exports at the moment. Wheat prices shot up last year as more food was consumed at home, record summer heat affected harvests, and Russian export quotas squeezed international prices. Russia is the world’s largest wheat exporter and saw a harvest of 132.9 million tons last year, a 9.7 percent increase over 2019. Despite the high production levels, prices for basic goods like bread and pasta began to rise significantly toward the end of 2020 because of the influence of export prices on the rates producers quoted domestically.

This was politically sensitive. Rising prices have reduced disposable incomes by nearly 5 percent. Russia’s response has been to impose stricter export quotas, higher tariffs on wheat exports, and to set price controls. All of these are likely to worsen shortages while trying to force trade partners to eat price increases and absorb inflation that would otherwise be happening in Russia domestically. That doesn’t inspire confidence for Chinese policymakers to expand Russia’s market access at the same time they’re improving it slowly for Central Asia’s food exporters. Even as Russia expands agricultural exports to China, it’s unclear they’ll be able to offset what could become a consistent, if small, trade deficit.

Reaching Maturity

Beijing faces a host of challenges at home in trying to preserve a sustainable recovery after the COVID crisis passes. Fears that a real estate bubble collapse could contract GDP by as much as 5 to 10 percent prompted curbs on bank loans for property, likely to slow down growth in the year ahead. More state firms are being allowed to default, deflating some risks in the financial sector but also worrying some investors. Newer lockdowns are also likely to hurt consumer spending, still weaker than it should be. While China plowed ahead in 2020 and lifted the Russian economy, that dynamic is changing in 2021. Slower growth lies ahead.

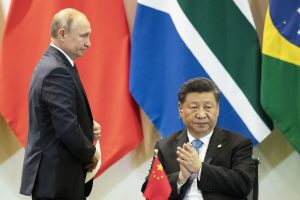

China’s economic maturation into a consumer economy is a gut punch to Russia’s economic model. Without strong external demand growth for oil and gas, Russians face a decline in their standards of living as state policy refuses to stimulate domestic demand while protecting large sectors from trade competition. Sino-Russian relations are long past the point of needing symbols of close ties. Follow the money. Most Chinese investors remain skeptical of Russian investments, most joint projects are politicized, and trade is still tightly controlled. China gains far more from the status quo than Russia.

Nicholas Trickett is an analyst covering oil and gas markets, trade and political economy, with a focus on Russia and the post-Soviet space.. He holds an MA in Russia/Eurasia studies from the European University on St. Petersburg and an MSc in international political economy from LSE. He writes a daily newsletter covering the political economy and geopolitics of COVID-19 and the energy transition in Russia and Eurasia called OGs and OFZs.